by the Rev. Robert C. Laird

This has been a difficult week for the seminary I attended,

the General Theological Seminary (or GTS)

in New York City.

Eight of the 10 full-time faculty staged a work stoppage,

hoping to bring the attention of the Board of Trustees

to a worsening conflict with the Dean,

and the Trustees responded by

“accepting the resignations” of the eight faculty

within 3 days of the strike.

It’s caused deep pain on all sides,

and is a mess that could well end up closing the school,

since GTS can’t afford not to have students,

and what bishop in their right mind

is going to send postulants to be formed as priests

at a school that’s going through the kind of convulsions

that have been seen this week?

The lack of trust between both parties is harrowing,

but the most devastating aspect is the effect on the students,

who are caught between the institution they love,

the faculty they respect and treasure,

and a conflict that doesn’t have much to do with them,

but is directly impacting their formation and lives.

The whole sordid story even appeared in the New York Times,

with an article in which neither side looks good,

and the whole Episcopal Church ends up looking foolish.

It’s a mess; it’s just a complete mess;

but Jesus shows us in the Gospel today

that complete messes,

even ones like this,

are not beyond his imagination.

Jesus gives us more than a parable today;

we actually get a full-blown allegory,

in which each word and image in the story

stands for something other than what it is in the story,

our Gospel doesn’t make a single point,

but makes a commentary on a set of relationships.

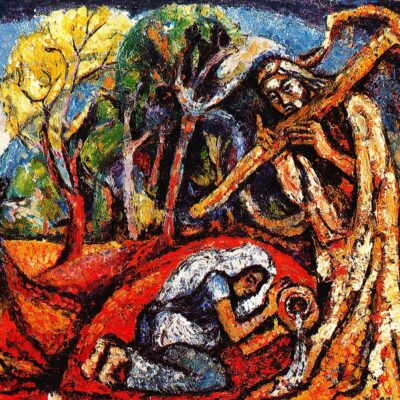

A landowner plants a vineyard,

gets the property all set up;

there’s a wine press, a lovely fence around it,

he builds a watchtower, gives it lots of homey touches.

This landowner then leases the property to tenants,

who are horrible, awful people;

they respond to the generosity of the landowner

with violence, which increases each of three times

that the landowner sends an agent

to collect the produce that the vineyard has produced.

The landowner even sends his own son,

whom surely the tenants will respect;

yet even he is beaten and murdered.

A preacher might usually be careful about taking sides,

contrasting the descriptions of a generous landowner

and horrible, evil tenants,

but it’s clear that that’s what Jesus is doing;

that’s part of why this is so interesting as an allegory;

Jesus is more clear than usual about whom he speaks,

and just what he thinks of those people.

Jesus is describing his own relationship with the authorities,

who are still livid at him for the events of the last week—

Jesus has thrown the whole of Jerusalem into turmoil

riding into town on Palm Sunday,

then throwing the money changers out of the Temple;

he’s only a couple of days away from condemnation,

and his destiny on Golgotha,

and the tomb that lies beyond that

(a tomb he will conquer, but at great cost).

In his allegory today,

God is the landowner, Israel is the vineyard,

and the chief priests and elders are the wicked tenants,

whose response in violence grows and grows.

God sends the former and latter prophets

to collect what is due,

but those prophets get nowhere in their task.

God even sends God’s own son, Jesus,

to reason with the wicked tenants,

and he foreshadows his own death later that week,

when he is thrown out of the vineyard and killed.

This is very on-the-nose of Jesus;

he’s laying it out in a way that was very clear and public,

and that enraged the chief priests and Pharisees,

because it was being done so publicly, and so obviously;

as the Gospel says, they wanted to arrest him then,

but they were afraid to,

because the people were beginning to see Jesus:

really see him, as a prophet, teacher, and messiah.

Now, allegory is a tricky thing to talk about,

especially in Jesus’ case,

because it’s so specific;

Jesus is talking in a particular time and place,

and talking to particular people.

Jesus is clearly talking to a group of people

on the Temple Mount,

namely the authorities,

and Jesus is trying to make them angry,

(and succeeding brilliantly at it, by the way),

and telling those authorities

about how they have rejected God,

even if they themselves don’t see it;

the chief priests and scribes

have gone off the rails,

and Jesus is telling them,

(or actually, the crowd tells them),

that the landowner will put the wretches to death,

that the penalty for their behavior is absolute.

Jesus is even driving the image home

by using an image from Isaiah

that would have been very familiar to the authorities,

which we read this morning;

the vineyard that God has created

has not yielded good grapes,

but rotten ones,

and it’s the fault of the authorities that Jesus is talking to.

So the authorities are angry,

and who can blame them?

Jesus has been both breathtakingly harsh

and exceedingly brazen in his attack.

Again, an allegory is trickier for us to talk about,

because it’s really about specific people

at a particular time and place.

But Jesus is clearly talking about

Israel rejecting God,

or forgetting about God,

which is a theme that runs

through the whole of the Bible.

And forgetting about God,

or directly rejecting God,

is something we today have a lot of experience with.

The outright rejection of God,

or the rejection of God for some sort of “spirituality,”

that doesn’t have much definition

is something we see all the time today;

folks in the Northwest are the least likely to believe

of anyone in our country;

put another way,

more of our neighbors here in the Northwest reject God

than anywhere else in the US.

That is clearly a problem that Christians here

need to look at honestly

(though it’s not something we’re going to solve today).

Of course, many don’t reject God outright

so much as dabble on the side;

saying one believes in God,

but really behaving like they don’t;

Elijah confronted the people

before the priests of Baal,

and told them to stop limping between two options;

humans have been keeping their options open

for millennia.

But the way that people are most guilty of rejecting God

in our time is by rejecting some of God’s people,

deciding that they are less worthy,

less human, less valuable than they themselves are.

Our nation maintained slavery for 246 years,

and then practiced slavery for another century beyond that.

We saw this summer how African Americans are

still treated as “other,” particularly by the police;

examples were everywhere,

in Ferguson, Missouri, in the death of Michael Brown;

in Staten Island, New York, in the death of Eric Garner.

We even see the effect of it here in Seattle,

like this last August, when Raymond Wilford,

a 25-year old African American

was trying to walk into Westlake Center;

he walked past a pro-Palestine protest,

and was attacked by a white pro-Israel agitator,

and the security guard emptied his pepper spray can,

because he figured it was the black guy who started it.

The security guy was wrong,

and all the witnesses on the scene confirmed that.

The truly tragic part of the whole incident

was a comment by Mr. Wilford after the incident,

who said “I’m used to it; I’m from the South.

“People here seem to be more secretive

about their not liking black people, or their racism,” he said. “I’m so used to it I don’t know what’s wrong

and what’s right half the time.”

When we see people as the other,

we deny God, who is present in all things, and all people,

even the ones that we don’t agree with.

In our Baptismal Covenant,

we promise to seek and serve Christ in all persons,

loving our neighbors as ourselves;

I’m confident we’re good at doing that well

in our individual lives,

with our actual neighbors;

but as a community we seem to do a pretty bad job

of ensuring our social structures

do the same thing,

helping our institutions

to respect the dignity of every human being,

instead of allowing indifference to breed contempt.

And it’s not just a problem in social institutions;

the seminary I went to in New York

has done just that this week,

the faculty and the trustees

have taken positions

that are nearly impossible to step back from,

and have escalated this conflict to a crisis

so quickly that the institution itself,

with its nearly 200 year history,

is on the brink of collapsing.

This is all the more shocking

because this is a place that is supposed to form priests

for service in the Church;

it really shows us how otherwise faithful, prayerful people

can go off the rails

like the chief priests and elders did in Jesus’ time;

after all, just like the chief priests and elders,

both the seminary faculty and the trustees

are faithful Christians,

trying to live lives centered in prayer and faith;

but once conflict arose and became public,

they retreated to their separate corners,

and dug themselves in so deeply

that they may never get out.

But God asks for more from us,

from our police, our institutions,

and from our church;

in Jesus’s allegory this morning,

he gives us a perspective

that makes it possible to reframe these conflicts;

when it’s a landowner and the wicked tenants,

we can easily see how wrong the tenants are,

and we can say, “God’s gonna be upset with them,”

and we can see clearly who is in the wrong.

When we’re in the middle of the conflict,

like the GTS faculty and trustees are,

with the students, and alumni, and the rest of the church

on the outside, trying to figure out what is really happening,

it’s harder to see the other side’s point of view,

even though that’s what God is calling us to do.

The Gospel today gives us a glimpse

into the world that Jesus lived in,

and into the messes that he had to deal with;

it also gives us a different perspective

on the messes that we create in our own day,

and on how we might make different choices

in the midst of those messes.

We believe that God dwells in each person we encounter;

the ones we agree with,

and the ones that we don’t agree with.

May God help us to see God’s self in each other,

that we might make God’s Kingdom known

through our choices,

and not tear the Kingdom down

through our rejection of God in each other.